Nonlinear Narratives and You

I’ve been talking about my bubble method of doing organization for a while now, but today I want to talk about something that’s useful for creative writers: nonlinearity.

Nonlinear stories can hold a lot of interest and have some practical advantages. It puts the storyteller entirely in control of pacing and the flow of information.

But it’s also difficult. The storyteller needs to be great at information control and keeping tones steady.

The bubble method is a simple content-agnostic organization style I’ve used for most of my writing. I’ve got a few articles you can check out if it doesn’t come intuitively to you, and you should also have read last week’s article about scene structures in the bubble method. My examples will use this methodology, but you don’t need to be a master of it yourself.

When to Go Nonlinear

Traditionally, storytellers have one scene that they are going to develop in its entirety, then they move through to the next scene.

There are a lot of advantages to this, but there are some fundamental drawbacks. It’s worth being fully aware of this before continuing, because many people see Pulp Fiction and think that nonlinear narratives are the best thing since sliced bread, when in reality they’re cool but add nothing unless you have the right story.

Traditional Narrative Strengths

- Very easy to comprehend.

- “Natural” storytelling method.

- Much easier to write.

- Works for most stories.

Nonlinear Narrative Strengths

- Makes audience think more.

- Tightly controlled pacing.

- Ideas when you want them.

- Easy dramatic irony.

For instance, the novel I’m working on was originally going to span two timelines, and combine a tragic story with a heroic story. You’d see the tragedy unfold at the same time that the heroic story unfolded (the heroic arc being the second, in chronological terms) to get a picture of two unique circumstances for the same character; first as she learned how to fail, and then as she learned how to succeed.

That’s a great way to build on the nonlinearity, especially when you have some twists to drop in regarding the relationships between characters, but it wasn’t working out in practice because the cost of it was higher; as someone who writes a lot but had never done a novel, the cost of the method outweighed its benefits for me.

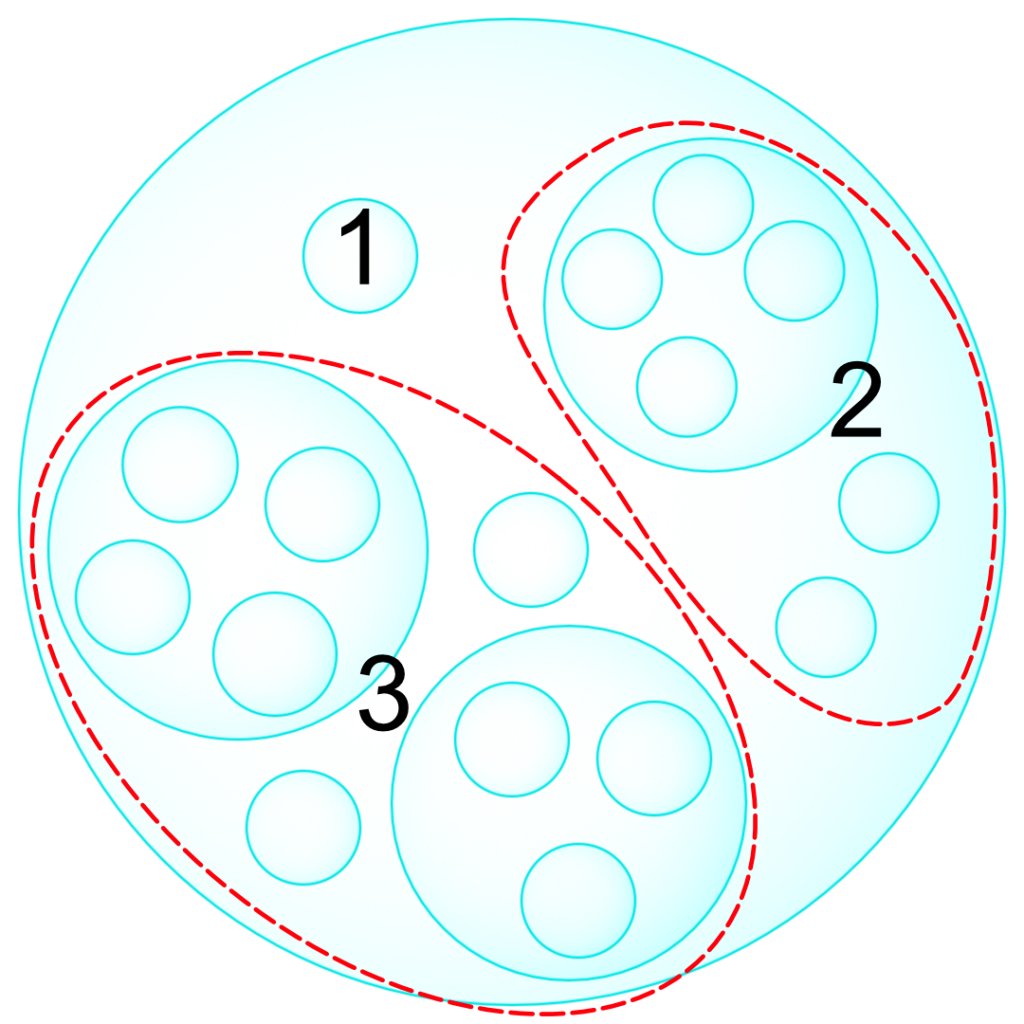

Now, let’s look at a very simple way that you can graph this out using the bubble method.

This is a very simple diagram, so it’s not really giving the best example of the power of nonlinearity.

You’ll note that I’ve set up a traditional diagram, where I’ve numbered off my scenes. Each scene has its own mood and subject. In the traditional method, you focus on one particular element for however long a scene lasts.

Breaking Points

You don’t want to jump into and out of scenes too often.

Make sure you know where you’re going from and to at all times. There’s something about being aggressive and experimental that has value, but it can also give your audience a headache and ruin your setups if you go too often.

My general rule would be this: don’t jump between small pieces that aren’t connected somehow. If you’ve got multiple storylines running, you can jump between them using the state of the dramatic arcs (e.g. jump from one storyline’s rising action to another storyline’s climax, and then back to more rising action), but if you’re just running through a single storyline you are going to be hard-pressed to find good break points.

Never force nonlinear storytelling for the sake of nonlinear storytelling. You’ll keep the English or Film majors and MFAs, but lose everyone else.

Another thing that you can do is simply make sure that you never (or rarely) jump within a scene, and instead link the scenes out of order. This makes Pulp Fiction appealing to wide audiences; it has a novel structure, but only a couple scenes (most notably the diner scene) are split.

You also probably don’t want to run an individual scene’s parts out of order. That’s excessively confusing.

What’s in a Scene?

One reason you might wish to adopt a nonlinear model is that it lets you split a single focus in two. Repeating an entire scene is usually not beneficial, though repetition and echoes can have their purpose in moderation.

By splitting a scene, we can avoid having to set the same mood and subject up again. This can optimize and streamline a story.

However, it’s also worth noting that this works better in some media than others; films can do this really well with things like color grading and visual cues, while text can fail to deliver on the nuance. The last thing you want to do is to have your audience fail to pick up on the way you delivered your scene.

Framing

It can also be useful to change the framing of events. There’s a somewhat tired method that involves opening a story at a point of peril for the protagonists (e.g. they’ve been captured by the bad guys) and then going back to an earlier time to watch events unfold.

At the end, the twist is that what initially seemed to be grim was Part of the Plan All Along (TM) and we see the heroes overcome the danger.

This is a “cheap” method that gets derided as a tool for hacks, but it’s “cheap” like a fast-food hamburger. Logically, we all know that it’s the cheapest product with a focus on mass production rather than any care and love, but it’s engineered to be appealing.

What this example of nonlinear storytelling does is simple: it gives us stakes right at the start of the story so that we know it’s going somewhere, even if there are slower scenes in the middle.

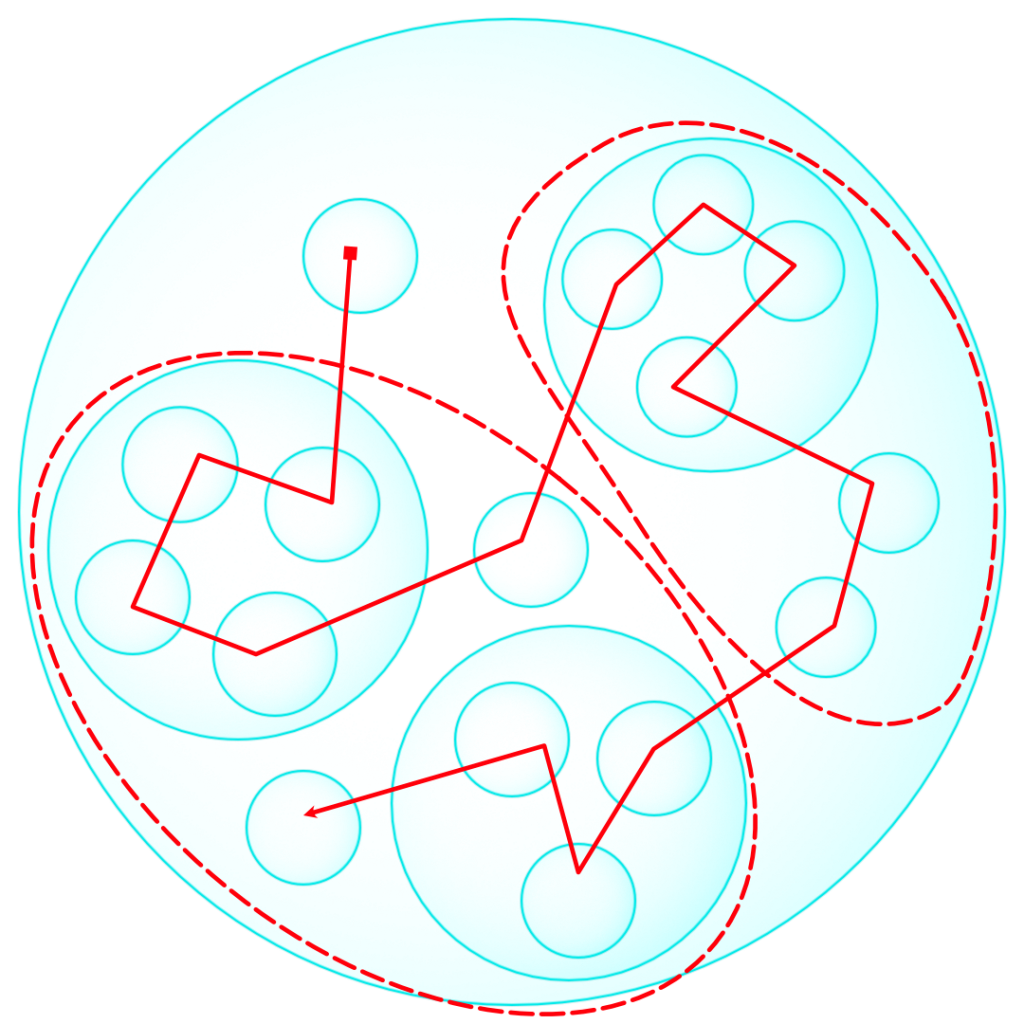

This is about as complex as the example diagram I gave, though obviously there are some questionable elements here.

Wrapping Up

Nonlinear structures let writers really play around with the stories they tell. It’s a high-risk, high-reward method that needs the right source material.

When crafting a nonlinear story consider:

- Don’t scramble scenes.

- Think of what each element is giving: how it builds tension, provides information, or satisfies an appetite for action.

- Remember that audiences have to invest more to decode the timeline in a nonlinear narrative. That can make a work more cerebral, or it can make it unintelligible.