Bubbles: Saving the Orphans

A couple weeks ago, I laid out my preferred method of organization. I use what I call a “bubble method” derived from a few different theories regarding text structure.

In case you missed it, here’s a link to it, and a brief overview:

- I use my system because it’s fast and simple.

- Although originally developed for nonfiction, it’s something that I’ve continued using as I move into more creative writing.

- It’s built around flexible fractal compartmentalization.

In short: you put each of your ideas into bubbles as a two-dimensional outline, with each bubble representing the content you need to make a point and the point itself. You put bubbles within other bubbles when they are sub-points of a larger point.

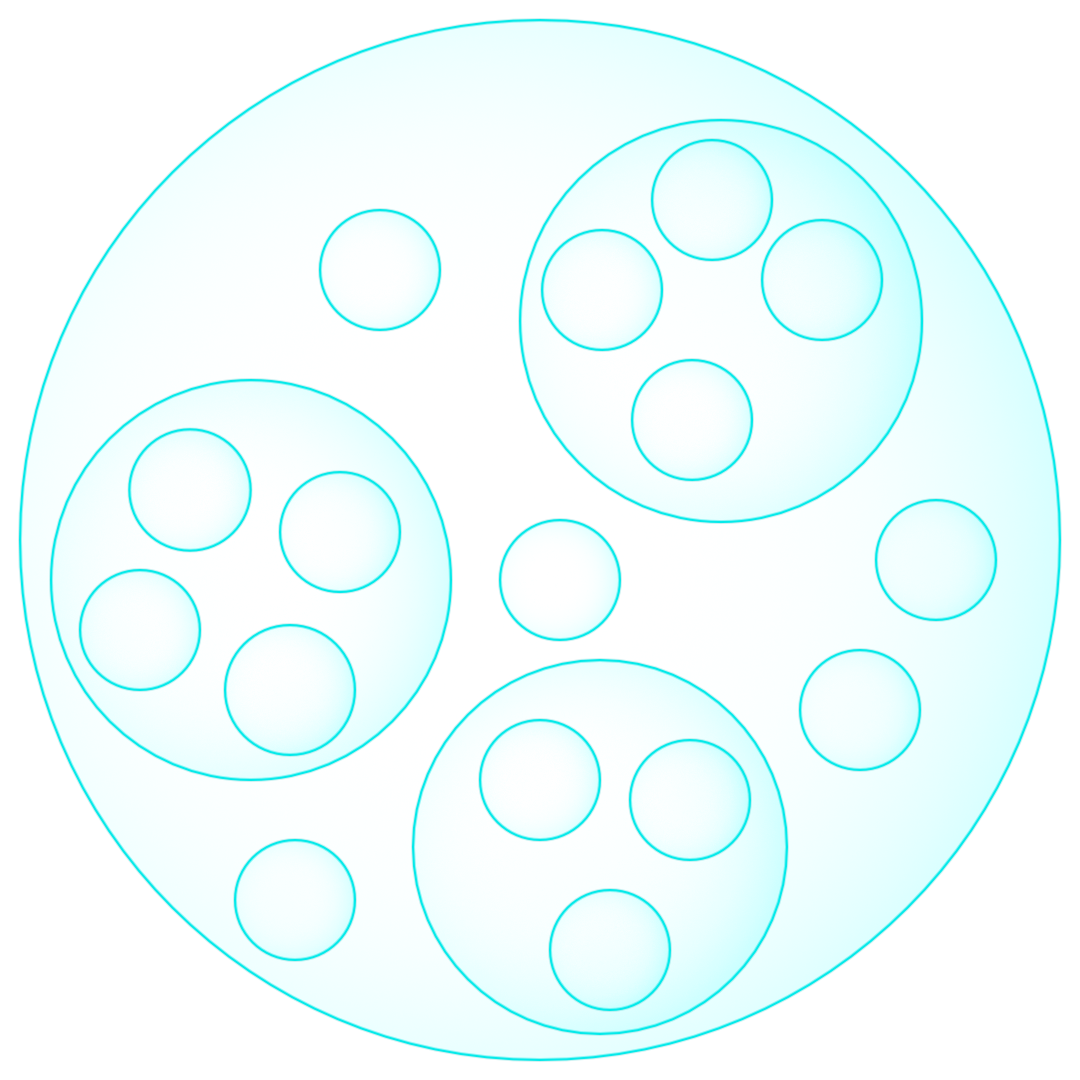

Today I’d like to talk about some advanced applications and nuance. I’ve even drawn a neat little diagram:

Bubble diagram: Outer shell, inner bubbles, orphan bubbles.

This could represent an essay like this, a short story, or a chapter of a book (which would itself be a larger bubble with other bubbles.

When I write, I go through a single bubble (and its sub-bubbles) at a time and then move onto the next, but there is some nuance to that.

Orphans

You’ll notice that there are some minor points that don’t go in larger bubbles. I call these orphans, and they’re something that can be problematic.

There’s a magic art to dealing with these, and it’s not an exact science.

You don’t want to have your big points all in one streak and then a bunch of orphans dropping at the end of a text. That creates a disjointed structure, and can create issues.

When I edit my writing, I often will cut out orphans, because they tend to get in the metaphorical joints and grind the whole thing to a halt. But sometimes they’re too important to cut, or they fit right in at a transition point.

Orphan bubbles make great transitions.

How?

The first way, which I will discuss with an example in a bit, is that bubbles can smooth over jarring gaps between things. This is almost exclusive to creative writing, though you might see it used in historical and biographical writing.

A secret to writing is that you’ve got to worry about your reader’s cognitive load. I don’t see people talking about this often, but it’s derived from a mix of educational and psychological theories that have become general practice in their fields.

If you’re writing something heavy, the reader will need to put a lot of effort into breaking it down and understanding it.

Orphans, if they are not technical minutiae that should be cut out of anything but an academic text, often have very little cognitive load.

To make an analogy to interval training for exercise, your bubbles can be either intense or relaxing. Use them appropriately.

Now, this applies to non-fiction more than creative writing.

In creative writing, the variation between larger bubbles and orphan bubbles serves to keep action flowing smoothly. A casual wise-crack or a moment of intense violence can set the scene for a new tone or mood.

These might still give the reader a breather, but they serve a different purpose.

Pacing in creative writing depends on a lot of factors, and one of the easiest places to see this is in film.

A Humble Example

The perfect example of this is the pencil trick scene from The Dark Knight.

The overarching bubble covering the whole scene is that the criminal underworld in Gotham has to adjust to the newly competent Gotham PD under Harvey Dent and Batman’s interference.

Next, we have a bubble involving the exposition for that.

The scene starts with Lau, the criminal underworld accountant, talking to the various criminal leaders about what they have to do to keep their money safe from the police.

They grumble about this, but come to believe him when he says it’s a good idea to keep their money secret.

Then, there’s a clever revelation that he already has squirreled the money away to Hong Kong, which is a character-building moment for Lau.

But there’s a problem. The criminal underworld isn’t really the central point of the film, and we don’t have our main characters yet.

Enter the Joker, and a tremendous little orphan bubble.

The pencil trick.

The Joker isn’t (yet) involved in organized crime, so he can’t be in the scene for the first part of the meeting. However, you want to avoid jumping scenes too quickly when filming (both practically for expense and artistically to keep the audience from getting confused).

We’re also in exposition and not main action, and the more exposition you can get done in a single loaded chunk, the better.

But that exposition is getting kind of boring, and the Joker (and moviegoers) detest boring.

So the Joker walks in sarcastically laughing, plants a pencil upright in the table, and says “How about a magic trick? I’m going to make this pencil disappear.”

When one henchman comes over to throw the Joker out, he slams the poor guy’s face into the table, and the promised pencil prestidigitation is complete.

The iconic discussion of what to do about Batman comes next, but we’ve seen all we need to make our point:

You have a way to mediate between two different larger points (organized crime worrying about money and the joint antagonists worrying about batman) along with a single moment of blink-and-you-miss-it violence to thrill the audience and wake up anyone who’s started to doze.

Wrapping Up

Orphan bubbles can be the hardest to do anything with because they’re not what people think of when writing.

A single key idea or moment that isn’t part of a larger point or scene can easily disappear in the mix of larger and more complicated parts of writing.

Master the use of orphans to vary pacing and provide a break from complicated or dull bubbles, and you can create a better work or scene overall.

Next week I’ll write about scenes and format, which is more appropriate to the creative writing use of bubbles, and the week after that I’ll discuss how to use bubbles to simplify one of the most daunting and rewarding efforts in creative writing: nonlinear narratives.